One of the challenges I encountered in adapting the Cúchulainn myths was that certain place names in Irish sagas do not correspond to modern names. Others are more easily identified. Sliab Fúait, beneath which Emer meets her Beloved in this chapter, is a peak in modern-day County Armagh, Northern Ireland.

Sliab Fúait is marked on this map, on the southern border of Ulster (artwork by Jim Fitzpatrick).

There is a place called Meadow of the Two Oxen in Armagh, but there is also one in County Galway. The ancient Irish were fond of animal place names. There’s even a Lake of Two Oxen (to say nothing of the meadows, mountains and lakes of Hounds, Bucks, and Boars).

Ballykeel tripod dolmen tomb in Armagh. This would have been very ancient even in Cúchulainn’s time.

47. Mournful Eyes

Emer awaited her beloved at the house in the Meadow of the Two Oxen. She awoke each morning thinking, This is the day I will see him. Each night she went to bed full of heartsickness and longing, in the knowledge that her beloved was rapidly earning the glory promised him in the prophecies, but was soon to end his life. Let me see my beautiful Cú again, before that happens, she prayed. All day she remained by the door in her warmest cloak, scanning the horizon, straining her eyes for the sight of his chariot. She was far too nervous to join Cepp on rambling walks in search of roots and herbs, or even to enjoy the respite from the tedious nursing of the Ulstermen. The only occupation that calmed her was spinning, for she could spin and look out across the meadow at the same time.

Then one afternoon, her heart thrilled to the sight of a chariot. As it came closer, a tiny, toylike object far across the meadow, she saw that it was drawn by a single dark horse. That is surely Black Sanglain. What of Liath Macha? She stared again, and made out the figure of a man with a crown of fiery curls in the chariot. That is surely Loeg. What of my beloved? Then a rider, mounted on a big powerful grey, appeared from behind the chariot and quickly overtook it, galloping toward the house. A red cloak… The spindle fell from her hand. She gazed at the rider, and her heart strained in his direction. She took a step, and then another, and then she was running madly into the tall, browned meadow grasses.

Soon he swung down from the steaming horse and seized her, whirling her about and whooping in delight as she clung to him. “Emer my sweet love! My dearest one! How I have missed you.” As he held her, she saw that the neck of his tunic was filthy, and gashed, and that blood was seeping from a recent wound.

“Let me look at you,” she said, trying to push him to arm’s length. Yes, sword slashes to the arms. The tunic sticking to his body where the blood has clotted. “You need a bath, and your wounds seen to. And new clothes. I’ve brought plenty.”

“How about some food for Loeg and me?” he countered. “And then I will come to your fine bed, and Loeg the biting satirist will search him out a place to sleep. The barn, I think!” He laughed, and they made their way back to the house.

Emer fed the men, but insisted on baths for both of them before they retired. Cepp helped her to bathe Sétanta and treat his wounds. These were mostly superficial, but numerous. What shocked her more were the healed scars which covered his body in a network of lines, some fine and some wide. Cepp ran her finger over a particularly shiny scar on his hard abdomen. “No mortal healer did this. Look, Emer. He took these wounds not a month ago, yet the scars are white and smooth.”

“Wee woman, that tickles!” complained Sétanta.

“Try this instead,” answered Cepp, threading her needle to close another, fresh wound which oozed gore just below the clean white scar.

All through supper, he whispered heated words to Emer of what he planned to do to her when they were beneath the bedcovers. Once in bed, however, he fell immediately into a deep sleep, lulled by the warm bath and the hot supper. She lay with him for a time, stroking his hair, and then rose to talk to Loeg, who looked handsome in a new green tunic, his wet hair curling about his head and shoulders. The fiery red curls were shot with grey now.

“Did young Fíacach return safely to Emain Macha?” he asked, his brow wrinkling in concern.

Emer assured him that the lad was well. “Indeed, he is fêted by his agemates, praised to the skies by his ailing father, and shamefully cosseted by his mother.” She smiled, her thoughts straying to the softly snoring occupant of the bed in the next room. “I don’t blame her a bit. But Loeg, how did things go after he left?”

“It is soon told,” he replied. “Medb offers her daughter Finnabair to each prospective champion, plying the man with drink and setting the comely girl on his knee. Her beauty is such that many agreed to fight, but none withstood the Little Hound. Finally, Medb desired Fergus mac Róich to be her next champion, but he refused on the ground that he is Cú’s foster-father. So she poured strong drink into him, and accused him of treachery, until he agreed to meet the Hound. He drove his chariot into the middle of the ford. ‘You must be under some strong protection, foster-father,’ said Cú, ‘to meet me with no sword in your scabbard!’ ‘It would make no difference even if I had one,’ said Fergus. ‘I’d not raise it against you.’ Then he asked Cú to yield to him, to spare him shame, for his sword was lost. ‘I think Ailill stole it from me when I lay in the woods with that bitch-wolf Medb.’ ‘I will pretend to run from you,’ answered Cú, and he retreated before Fergus’ chariot to the edge of the swamp, as the army jeered. But Fergus did not strike a blow, nor kill his opponent, so he did not win his cause. A new champion comes forth tomorrow.” Loeg looked grave, and Emer asked, “What champion?”

“Ferdiad mac Dámon, of Connacht.”

“Ferdiad? He was a school-fellow of Cú’s, was he not, when they both learned weapon feats under Scáthach?” Indeed, her beloved had spoken often of this man. Only one other, Conall Cearnach, was as dear to him. Yet the friendship of Ferdiad had never been forgotten, though he was a man of Connacht, the traditional rival of Ulster.

“Aye. Fast friends they were, and Ferdiad fought at his side against Aoife’s warriors. Cú is heartsick at the news. He can hardly believe his old friend would come against him, but it is Medb’s doing. Fergus told us that she offered him Finnabair’s sweet breasts, and plied him with drink, and harried him until he agreed.”

“Surely Cú can best this man, just as he has the others?”

“Yes…” said Loeg doubtfully, “if it were another man of the same strength. Cú says they are evenly matched. Yet I fear his love for Ferdiad will dim his hero’s light.”

“That must not be,” said Emer. Then she rose, and slid back into bed beside her beloved, though she did not sleep. Later in the night he woke, and kissed her tenderly. He made to roll onto her, and she said, “No. Cepp said you must sleep on your back tonight or your wound could open.”

“What, Emer? You would deny me your body on this of all nights?”

“Not at all, my Cú. Lie back. Conall Cearnach’s wife Lendabair told me of a different way to make love. When we pledged ourselves to wed, you said that we would learn all the ways of love together, but what of this?” She straddled his hips, and touched his man’s part, which strained upward with all its might.

“Emer, my foster-father Amergen taught me how a man of rank behaves toward his wife. He said that a hero must never come to his wife intoxicated, never handle her roughly, and never ask her to demean herself with the postures of a tavern-wench.”

“Husband, Lendabair is no tavern-wench. Why did you listen to Amergen, that waggle-bearded old stick, when even his own son Conall knew better? Fergus mac Róich, now, he is a man of the earth. What would he say?”

“Fergus? Why, that rascal would insist that he needed a demonstration before he could judge. Remind me never to let him near you.” He grasped her hips as she settled on top of him.

“Why, it’s just like riding Black Sanglain,” she decided after a moment. “But better.”

Early the next morning, she plaited her beloved’s hair and arrayed him in the finest of the garments she had brought from Emain Macha. On Loeg she bestowed a rich green cloak.

“Fight well, and return to me,” she told Sétanta. He kissed her and smiled, but his eyes were mournful.

Copyright 2017 by Linnet Moss

Notes: This chapter illustrates Cúchulainn’s close friendship with his charioteer Loeg, who is also a part-time satirist! Loeg is the elder man, and completely devoted to Cúchulainn–perhaps the only person who truly understands him. There are stories about Loeg which I don’t include in this novel. In Serglige Con Culainn, his master sends him to the Otherworld to find out what it is like and report back (an assignment which he dutifully carries out).

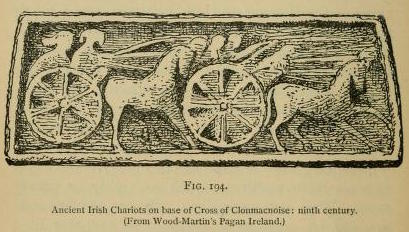

This is the oldest image of Irish chariots I could find, from ninth-century Clonmacnoise. Warriors never drove themselves. They needed a charioteer so they had their hands free to fight.

A sweet love story admidst all the fighting LM.

Thanks Lisa. That is one thing gained from adopting a woman’s perspective 🙂