Tags

Andrew Garfield, Ciarán Hinds, cicada, film adaptations, Liam Neeson, Martin Scorsese, Shusaku Endo, Silence

In Martin Scorsese’s film adaptation of Silence, the 1966 novel by Shusaku Endo, we first see a black screen and hear the song of cicadas. Once again at the end of the picture, the screen is black and the cicadas are heard. I suspect that this reflects the symbolic role of the insect in Endo’s story of Catholic missionaries struggling to plant their faith in 17th century Japan, where Christianity has been brutally outlawed.

An abandoned Japanese village in “Silence.” All screen caps are by Linnet, from the official trailer.

Here is what Lafcadio Hearn had to say about the cicada in Japan: As the metamorphosis of the butterfly supplied to old Greek thought an emblem of the soul’s ascension, so the natural history of the cicada has furnished Buddhism with similitudes and parables for the teaching of doctrine. Man sheds his body only as the semi sheds its skin. But each reincarnation obscures the memory of the previous one: we remember our former existence no more than the semi remembers the shell from which it has emerged… This cast-off skin… in Buddhist poetry… becomes a symbol of early pomp, -the hollow show of human greatness.

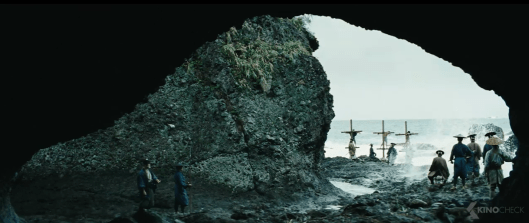

In the film, the mountainous coastline of Taiwan stands in for Japan.

Throughout Endo’s tale, which takes place during the summer, the cicada sings at key moments. It first makes itself heard when the exhausted young Jesuit priest, Rodrigues, wandering in the woods, stares into a pool of water and thinks of the face of Christ, “the most pure, the most beautiful that has claimed the prayers of man.” Rodrigues’ momentary vision of himself as Christ dissolves, and instead he sees “a tired, hollow face,” stubbled, thin and dirty. He laughs hysterically, grimacing at the water.

Rodrigues sees an exalted image of Christ in his own reflection.

The cicada’s song, then, may announce Rodrigues’ vainglorious mission, his delusional self-importance: he will save the Japanese by converting them to the one true religion, and he himself will face a glorious martyr’s death.

Andrew Garfield plays the young and handsome Father Rodrigues.

Adam Driver is his companion, Father Garupe (Garrpe in the book). Garrpe chooses the orthodox path prescribed by the Church, but a different fate awaits Rodrigues.

Ciarán Hinds plays Father Valignano, the superior who tries to dissuade the two young priests from going to Japan. Later in the film, he has a most unexpected role.

Spoiler alert: hereafter I discuss key plot points in both book and film.

Events turn out very differently than Rodrigues expected. Instead of gaining a martyr’s glory, he is forced to watch as his flock of “hidden Christians” is tortured, dying in agony, so the authorities tell him, for his sake, not for Christ. Throughout it all, Rodrigues’ god is silent, offering no help, no sign in the face of such deep suffering. Rodrigues wrestles with theological doubts about the mission, as well as shame at the physical disgust he feels toward the people he is meant to serve.

A welcome from eager “Hidden Christians.”

The officials’ goal is to make Rodrigues himself apostatize, thus shaking the faith of the Japanese converts. In high summer, the cicada sings again as Rodrigues witnesses the horrifying execution of an old man, who is decapitated and dragged away, leaving a trail of blood:

Just as before, the cicadas kept on singing their song, dry and hoarse. There was not a breath of wind. Just as before, a fly kept buzzing around the priest’s face. In the world outside there was no change. A man had died, but there was no change.

A Japanese Christian martyr. From the safety of the woods, Rodrigues watches him led away.

Has the cicada, a Buddhist symbol of the immortal soul, been drained of meaning? Or is the problem Rodrigues’ own inability to grasp Japanese culture, and the incommensurability of Buddhism with Christianity? This was one of the central questions for Endo: was Catholicism truly a universal religion, or would it be bound to fail in cultural environments where its most basic assumptions were not shared? In other words, could the cicada ever be re-fashioned as a symbol of Christian rebirth and resurrection?

The terrifyingly winsome inquisitor Inoue (center) is played by Issey Ogata.

Rodrigues and his companion Garrpe have come to Japan to find their old teacher, Father Ferreira, who (rumor has it) is an apostate, “lost to the Church.” When he finally meets Ferreira, Rodrigues learns to his horror that the story is true. Ferreira concluded that the Japanese were unable to understand the Catholic concept of a transcendent God. “The Japanese,” says Father Ferreira, “imagine a beautiful, exalted man–and this they call God.” Ironically, this is the very error which Rodrigues himself has cherished for most of his life, devoting himself to a mental image of Christ as the most beautiful, the most exalted of men.

Liam Neeson gives a stunning performance as Father Ferreira.

In the screenplay by Jay Cocks and Martin Scorsese, Ferreira says instead that the Japanese have mixed up the Christian god with the Sun god: they cannot imagine an existence which “transcends the realm of nature.” The men and women who died such agonizing deaths did not give up their lives for Christianity, but for “the wrong god.”

Did they die for “the wrong god”? Japanese martyrs crucified in the sea.

Ultimately, in the film’s most moving scene, Ferreira assists Rodrigues to perform the physical action required of apostates: placing his foot on a tablet called a fumie, which bears an image of Christ. By doing so, Rodrigues will give up all his pride, his hopes and dreams for the mission of converting the Japanese. But he has the chance to end the agony of many, including the five Christian men and women in the stockade, who have been hung upside down over pits of excrement. They have already apostatized, but they are dying, says Ferreira, for Rodrigues and his pride. Rodrigues, the last Catholic priest in Japan, can help to end the persecutions.

RODRIGUES: I believe!

FERREIRA: You believe in yourself! You set yourself above them. It’s your salvation that obsesses you, not theirs. You dread to be the dregs of the church, like me. Is that your way of love? A priest should act in imitation of Christ. If Christ were here… If Christ were here, he would have acted. Apostatized. For their sake.

RODRIGUES: No, no. Christ is here. I just can’t hear him.

In the book, when Rodrigues looks down at the face of Christ on the fumie, he sees something new: “Before him is the ugly face of Christ, crowned with thorns and the thin, outstretched arms. Eyes dimmed and confused, the priest silently looks down at the face which he now meets for the first time since coming to this country.” At last God ends his silence, speaking to Rodrigues from the fumie: “Trample! …It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.”

In the film, Christ is voiced by none other than Ciarán Hinds, who envelops Rodrigues in comforting paternal love:

CHRIST: Come ahead now. It’s all right. Step on Me. I understand your pain. I was born into this world to share men’s pain. I carried this cross for your pain. Step.

As dawn is breaking, Rodrigues places his foot on the face of Christ, and the cock crows in the distance, heralding his betrayal.

Throughout the book, the figure of Judas haunts the narrative in the person of Kichijiro, the Japanese apostate who guides Rodrigues and Garrpe to the community of hidden Christians. Rodrigues scorns Kichijiro for his “servile” behavior and feels disgust at the way the man keeps falling from grace, then crawling back to beg confession of his sins. In cinemas, Kichijiro’s abject repetition of this process actually draws laughs from audiences, who share Rodrigues’ contempt–despite the scenes showing how Kichijiro’s entire family was burned to death before his eyes.

Kichijiro, the Judas figure, is played by Yosuke Kubozuka.

One of Kichijiro’s many groveling requests for absolution.

What these audiences don’t grasp is that they are laughing at themselves, for Kichijiro represents the human condition, the inability of anyone to be completely free from sin. For the community of Hidden Christians in Japan, whose choice was to step on the fumie regularly, or be tortured to death, Judas was a figure of special meaning. When every Christian is also an apostate, a betrayer of Christ, Judas’ weakness, and Christ’s direction to Judas (“Friend, do what you came to do,” MT 26:50) receives a different interpretation.

A fumie, a bronze icon of Christ set into a wooden frame. This example is much worn, either from touching by the faithful or being stepped on. It was sold at Christie’s in 2011.

Ultimately, Endo’s novel advocates a universal Christian ideal, but not one which corresponds to the expectations and teachings of the historical Catholic church. As Ferreira tells him, “There is something more important than the Church.” This is the paradox in Silence, that denying Christ could be the most Christian act of all.

Father Rodrigues ministers to a young girl.

Thank you for this insight into this film and its symbolism. Interesting to see that Liam Neeson is still able to act !

Yes, he’s quite impressive here!

Thanks, an absolutely exquisite summary and analysis of this haunting and beautiful film. There is so much in this film that indirectly (but importantly) references the book that is easy to miss if you haven’t that prerequisite. Your summary should be read by everyone who has seen the film but not read the novel!

Thanks, Karen! The film stands on its own, but I think the novel is a masterwork, and reading it helps illuminate what Scorsese is doing in the film. I liked it that he keeps quite closely to the book, but not slavishly so. At the end, he’s able to add his own spin, suggesting that both Ferreira and Rodrigues remained lifelong Christians. I thought the book was more ambiguous, especially with regard to Ferreira.

Where did you find out that Christ was voiced by Ciarán Hinds? I have been looking for this information but couldn’t find it.

Well, I guess you’ll have to take my word for it. I’m a fan of his and I’ve watched and listened to virtually everything he’s done that is publicly available, including his audiobooks, as well as numerous stage performances. So, I found his voice unmistakable 🙂

That’s good enough for me. He’s not credited, I don’t think. For a minute, I was thinking Scorsese might have gotten Willem Dafoe to do it as a callback to Last Temptation. But this makes more natural sense.

He’s not credited. I watched all the credits carefully to see if he would be. A very interesting move by Scorsese. Especially since CH has played the Devil more than once in his career😀

Yet another layer of ambiguity. I love it.