Tags

I am fond of classic book and magazine illustrations, especially the romantic ones from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Among my favorites are Howard Pyle, Maxfield Parrish, Arthur Rackham and Jessie Wilcox Smith. While researching illustrations of Cúchulainn, I came across Stephen Reid (1873-1948), who was born in Aberdeen. He illustrated children’s books, including Eleanor Hull’s influential The Boys’ Cuchulainn. You can find this book scanned, with its magnificent illustrations, at the Heritage History site.

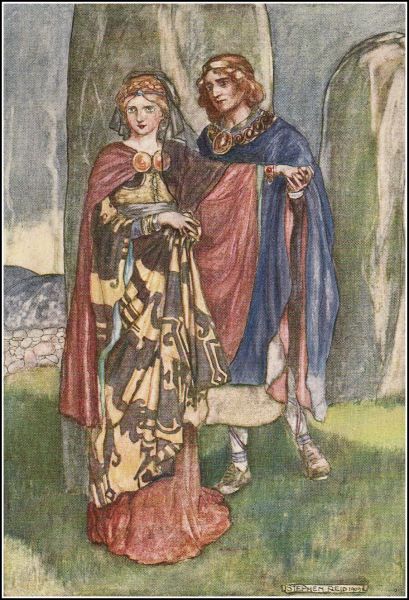

Cúchulainn wooes his bride Emer. Illustration by Stephen Reid for Eleanor Hull’s “The Boys’ Cuchulainn.” (1910)

10. Comeliest of Men

“I do not wish to marry Lugaid,” said Emer calmly. “He is a king, of course, but I do not hear him numbered among the great warriors of Éire.” She sat at a small table with her hand loom, fashioning an intricate braid of blue and green, interspersed with gold threads, to ornament the edges of a new tunic for her father. This she had already woven on the big upright loom, from wool dyed a deep blue.

The intended recipient of this kingly garment glared at her. “Then who?” he asked. “Are you pining for some other? Is that the cause of your pigheadedness?”

“I haven’t met him yet. But he must be uncommonly fierce, a great warrior,” she said firmly. “And nimble, and quick. He must excel in the manly dance with spear and shield. Yes, he must be as skilled in every feat of manhood as I am in all the womanly arts.”

“You value yourself highly, my daughter,” said Forgall the Wily. “I find no fault with this pride, seeing that you are my blood. But you’d do well to remember that pigheadedness is not counted among the womanly arts. And that I am the master in this house.”

The next day was pleasant, one of the first warm days of Spring. Emer sat out of doors among the maidens of Luglochta Loga, teaching them the skills of spinning, fashioning the braid, and embroidery.

“Emer, why do we embroider our garments with spears that sprout yew leaves and berries?” asked the youngest girl, Caoimhe.

“We live in the Garden of Lugh,” answered Emer. “The symbol of Luglochta Loga is the quickening spear.”

“You’ll learn all about the quickening spear when you get older,” said Róisín, giggling. She was to marry her cousin Corrin in a few weeks, and the pair lost no opportunity to sneak off together when Róisín’s mother wasn’t looking. She had confided to Emer that Corrin possessed a great club of a manly part, as thick as a chariot pole.

Emer’s sister Fiall sat across from her in the circle, holding the warp of her hand loom tight by a loop on her toe. She looked up and past Emer. “I see a warrior in a chariot. He’s coming toward our lands.”

“What manner of horses has he?” asked Emer.

“A high-bounding pair, impetuous and fierce, with curling manes. One gray, and one black.”

“That is well. What manner of chariot has he?” she asked, blushing slightly at the thought of the chariot and its pole.

Fiall squinted in the light, an expression which did not flatter her. “Wait, he’s turning into the drive. A fine chariot, with carved wood and wicker, all in white and silver, a copper frame, and a long pole of silver. A gilt yoke, and plaited golden reins.”

“That is well. What manner of man is he?”

Fiall’s face was alight now. “A dark, sad man,” she reported. “Not large, but comeliest of the men of Éire, sister. He wears a beautiful five-fold red cloak, with a great round brooch of gold. A hooded shirt of twilled white and red, like blood on snow. His black hair glints in the sun with a sheen now deep blue, now rose-hued; his two brows are black as the crow’s wing. A great sword with a gold hilt rests against his thigh, and a blood-red spear is fastened to the copper frame of the chariot. He carries a silver-bound shield, inlaid with beasts, I think.”

“That is well,” said Emer, intrigued by the description. She wished to know more of this man.

“The charioteer is a fine man too,” continued Fiall. “Slender, long-sided, much freckled, with fiery curls, and a ring of bronze on his brow to keep them in check.” Emer heard the pounding of the hoofs and the clanging of the chariot as it came. The sound made her heart leap. Now, as she kept her face modestly lowered over her embroidery, she heard the warrior’s footsteps behind her, and he walked into the midst of the circle. “Blessings on you all,” he said, whirling about in his festal array so they could all admire his magnificence.

He stopped suddenly, facing her, and she lifted her head proudly. “May Lugh make smooth the path before you,” she said. It was the blessing of her house.

“May you be safe from every harm,” answered the warrior formally, catching and holding her gaze. He had extraordinary eyes which shifted their color as he changed expression. But although the eyes danced, they were sad.

“Which way did you come?” she asked.

“It is soon told,” said the warrior. “Loeg and I came from the Covering of the Sea, over the Great Secret of the Men of Día, over the Garden of the Morrígan, over the back of the Great Sow, over the Marrow of the Woman Fedelm, here to Luglochta Loga.”

He spoke to her in riddles, but they were no mystery to Emer, whose father had seen to it that she was well educated. The Marrow of the Woman Fedelm was the Boyne river, north of her home. The Back of the Great Sow was Druimm nEbreg, where the shape of a sow misled the sons of Míl when they invaded Éire. The Garden of the Morrígan was Ochtur Netmon, given to her by the Dagda. The Great Secret of the Men of Día was the Marsh of Dolluid, where the Tuatha Dé Danann plotted their battle against the Fomori. And the Covering of the Sea was the Plain of Muirthemne, in the land of the Ulstermen.

“You have come far, warrior, on your journey south. Clearly you are one who knows his way.” For she divined from his place of origin at Muirthemne that he was Sétanta, sister-son to Conchobar of Ulster, and this was the very meaning of his name.

He smiled at her. “I was told that of all the women of Éire, only Emer daughter of Forgall possessed the six womanly gifts of beauty, voice, speech, craft, wisdom, and chastity. As Tara is above every hill, they said, she is above every mortal woman. Such a woman as this, and no other, is a fit wife for a champion of Ulster.”

Emer inclined her head in agreement. She knew her own worth. This Sétanta, being a man, and a young one at that, did not yet understand that the most valuable gifts a woman brought to her husband were friendship, and loyalty, and love. But men could learn, though slowly, and often in fits and starts. Her mother had assured her that this was the case. “What account do you give of yourself?” she asked him.

“My foster fathers were many. Sencha the wise taught me judgment, Blai the lord of lands taught me hospitality, Fergus the warrior taught me valor and the sheltering of the weak, Amergen the poet taught me praise and cleverness. In the House of the Red Branch I came to the knee of Conchobar of Ulster, who taught me splendor, boldness, and battle prowess. And for the sake of my mother Deichtire, Cathbad the druid trained me in the excellencies of knowledge.”

“Very impressive,” she replied in solemn tones. “I cannot boast such a wealth of foster parents, but I was brought up to guard the flame of honor and the ancient virtues of the women of Éire.” As they were speaking, his gaze moved from her face to her breasts. The day was warm, and she wore a gown of dyed linen fashioned in two layers, for modesty. Yet her neck and the upper part of her bosom were bared.

“Fair is the plain, the plain of the noble yoke,” he said to her, and his words pleased her in mind and body.

“No one comes to this plain who has not slain a hundred men.”

“Fair are the twin doves who nestle together,” he said.

“No one snares these doves, who has not mastered every feat of manly excellence.”

“Fair and sweet are the swelling fruits of summer.”

“No one tastes of this fruit, who is not numbered among the chariot-chiefs of Éire for his deeds of valor.”

“I swear, Emer, my deeds of valor, my battle-feats shall be recounted among the glories of the men of Éire before I return.” They stared at each other, and she realized that her heart was pierced through and through. There was a feeling of recognition, too, as though she had met this man before.

She said to him, “Your pledge is heard, your offer is taken, your word is accepted.”

Without another word, he swept out of their circle and leapt into his chariot, where the fiery-haired charioteer, Fiall later told her, had been listening to this conversation with a quizzical look on his face. The pair sped off in the waning light of day, and the maidens prepared to make their way indoors.

Copyright 2016 by Linnet Moss

Notes: Tochmarc Emir is one of the most beautiful of the Irish sagas. It contains a lengthy scene in which Cúchulainn wooes Emer with complicated riddles involving Irish place-names, such lore being a favorite of the saga authors. Unfortunately, most modern translators have omitted this part because of its difficulty for readers. I offer a simplified and adapted version of Cúchulainn’s first meeting with Emer, which I hope captures some of the poetry of the original. But it’s worth noting that the original has an earthy quality as well. I have adapted Eleanor Hull’s version in which Cúchulainn praises “the plain of the noble yoke.” At least one other version has Cúchulainn praising Emer’s bosom and predicting that “in that sweet country I will rest my weapon.”

Emer’s family lived at the “Gardens of Lugh” which is identified with the Dublin area and specifically the town of Lusk.

The medieval church at Lusk is attached to the round tower, which dates to the ninth century.

How very beautiful and ancient. I would rather be wooed with riddles than with a text full of emojis.

I couldn’t agree more, Lisa. Emojis are fine in their place, but overuse of them has a negative impact on people’s ability to express themselves verbally. I teach an online class, and I have to remind the students not to use emojis and texting abbreviations like LOL in their formal writing assignments.

It makes me wonder whether the modern Irish have taken to emojis as much as others, since they still take such a delight in language.

Thank you for this text Linnet. I have just seen a first edition of Sylvia Plath in a beautiful book shop, but too expensive for me (3,750 euros)

Wow, Sylvia commands a high price. I’m amazed when I think of all the handmade Renaissance books you can buy for that amount.

It is Sylvia or it is the bookshop, I suspect it is the bookshop and its location 🙂

lovely retelling of this ancient story, which captures both the poetry and the earthiness of the original myth. People were more direct then, I guess. In some ways it may seem sad that we have lost this form of romantic courtship, but I think most modern women would not be pleased if a stranger (no matter how attractive) approached them, stared at their breasts and talked about their chastity, and what he would do about both! Just sayin’…

Haha! Yes, it *is* rather direct, isn’t it. Perhaps it is only an epic convention for things to move so quickly (as opposed to, say, a novel). Or perhaps it’s just a case of mad love at first sight 🙂

What an extraordinary story! I like the list of virtues, talents and knowledge 🙂 And the wooing in riddles 🙂 Earthy and not, at the end o the day she knows her value and takes it as a compliment.It’s almost more shocking that she sends him off to kill more men to make a name for himself 🙂

Thanks Hari! Yes, Emer is a fierce woman from a warrior culture, so she wants her man to prove himself in battle. Not a problem for Cúchulainn, LOL.

Pingback: Culann’s Hound 15: Bachelor Farmers | Linnet Moss