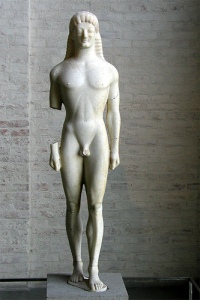

The Tenea kouros (youth) was sculpted around 560 BCE and originally served as a grave marker. He has the enigmatic “Archaic smile” of early Greek sculpture. Some say the smile resulted from the technical challenges of carving marble, and some believe it was an attempt to make the sculptures seem more lifelike. Others find a deeper meaning in the smile, as though the statues know some profound yet amusing secret which they haven’t seen fit to share with us… yet.

2.

Andy waited for Max to appear within the long chute that periodically discharged passengers outside the security gate. She saw him before he noticed her, and she watched as he came closer and closer, his head turned slightly to one side to check out the series of black and white photographs of public art in Philadelphia. Though she ran into him every few years, she was always slightly shocked to see that he wasn’t the same long-haired, rangy beanpole she’d known in Madison. During his thirties he had filled out, as men do, and he was big, with powerful legs, broad shoulders, and a slight tummy that reflected the pleasure he took in food and drink. She smiled, remembering his voracious appetite at the age of twenty-six. He had been devoted to Hostess products, and she cherished a mental snapshot of him opening his door to greet her, shirtless and with a mouth full of Twinkie. He had immediately offered her the twin pastry, in his generous way, as though it was made to be shared.

Nearly twenty-five years later, Max still possessed the sexual magnetism she remembered so well, even though his face had always been more ruggedly masculine than handsome. His black hair was salt and pepper now, short, and parted on the side. He was clean-shaven, but by the end of the day one could discern a shadow. He wore a suit, as always whenever she saw him these days, but no tie, and his collar was open.

“Andy! What are you doing here?” Now he was upon her, and gave her a hug and a kiss on the cheek. Max was the physically affectionate type. Always had been.

“I’m here to pick you up,” she said.

“What? I was planning to rent a car. There’s something I’d like to do while I’m here— that’s why I came early.”

They were walking now toward the baggage claim. “Oh. I don’t want to intrude, but I’m free. I can take you wherever you want, and save you the cost of the car.”

He considered this. “That’s very good of you. Do you know where Rimini is?”

“Oh, yes. It’s the next town over from Parnell. A little town that time forgot. It’s still got its original Main Street from the nineteenth century, and though a lot of the storefronts are empty, the architecture is beautiful. Why? Is that where you want to go?”

He nodded. “I think so.” The bags started to travel down the belt, and she waited while he retrieved a suitcase.

“Let’s get you checked in at the conference center, and then I’ll take you out to Rimini.” She wondered what he could possibly want to see there. It was a charming small town, but that was all.

She waited in the lobby as Max went up to his room to stow his bag. “Does Rimini have more than one cemetery?” he asked, as they emerged from the hotel. “I think my grandmother may be buried there.”

“Oh, I see,” said Andy. “Yes, there are at least two cemeteries. John and I used to go out there to walk in the bigger, older one, and then have lunch. You know how he loved walking.”

“Mmm, I do,” he said, his brow creasing slightly at the mention of John. “How’re you getting along, Andy? Are you okay?”

“Sure,” she said shortly, trying to think of a way to change the subject. This was not the time to launch into a discussion of her psychological issues.

“Seeing anyone?” he persisted.

“Max,” she said.

“Well, are you?”

“How is it any of your business?”

“So you’re not,” he nodded, as though she had confirmed it. “Why not?”

She exhaled in annoyance. “Drop it or I’ll take you back to Parnell. You can rent a lovely bicycle there.”

“Sssh, there now. No need to get tetchy with me.” He spoke soothingly.

“No need to pretend you’re the Horse Whisperer,” she told him. “And I’m not tetchy.”

“Whatever you say.” She heard the smile in his voice as she pulled into the parking lot of the cemetery.

***

I remember dressing carefully whenever I went to John’s class. I usually wore a skirt, one of my long plaid pencil skirts, with a lambswool sweater and boots if it was winter, or a lined cotton skirt and twinset in spring. One day, his office was very warm, and I was hot from rushing across campus so as not to miss a minute of his precious office hour. I removed my pink sweater and held it in my lap; underneath was a matching tank top, and my mother-of-pearl choker. As I listened to John discussing Botticelli, the sweater fell unheeded to the floor, and he leaned over to retrieve it, gravely returning it to me as though it was a precious leaf from an illuminated manuscript. When I took it from him, and our eyes briefly met, I became aware for the first time that the relationship was one of eros, on my side at least, and very possibly on his.

Even then, when I realized that I was falling in love with him, and understood that he found me attractive as a woman, it did not at first occur to me that there could be anything more. I only knew that I looked forward to our meetings, prepared for them, rehearsed at night what I might say to evoke that look of amused approval he sometimes bestowed on me.

I didn’t know his age; I assumed he was nearing fifty. Later, when I learned that he was a full decade older than that, it didn’t matter. Even at fifty-seven, John was attractive to me. He was one of those tall, slim, elegant men who wore his clothes well, and he had lovely clothes, tweeds and beautifully cut wool serge suits and even a seersucker suit in summer. True, he was grey at the temples, but his coffee-colored hair showed no signs of thinning. He had a sensuous, intelligent face, with a long, masculine nose and a firm chin. His blue eyes twinkled like sapphires, especially when he smiled and showed his fine, white teeth.

***

Though John was an American, he had spent much of his childhood in England where his father worked after the war for Daimler, and then Jaguar. He had been educated at Oxford, and it showed. An Anglophile from the time I was old enough to appreciate classic movies and read novels, I never tired of listening to him speak. With his slight accent, his old-fashioned, rather formal clothes and manners, and his mordant wit, he was like the hero from some sophisticated postwar Ealing Studio comedy— a taller, lanky Alec Guinness, perhaps.

John was an intellectual historian, and tenured in the faculty of history, but he would have been equally at home in a department of literature, or foreign languages. I often wondered whether there was anything he hadn’t read. He knew Latin, German, French and Italian, and could get by with a dictionary in ancient Greek, Russian, and Spanish. When I arrived in Madison, I was advised not to miss his seminar on the development of connoisseurship in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a phenomenon which was directly related to one of my own interests, Greek vase painting. John included in his seminar a case study of Sir John Beazley, the archaeologist and art historian who had almost single-handedly created the modern system of classification for Greek vases, and identified individual vase painters by means of subtle stylistic details that could be traced from one vase to the next: here, the distinctive shape of an ear, there the way the bones of the knee were delicately drawn on a figure in profile. John, I was thrilled to learn, had met Beazley himself at Oxford in 1955, the year before the great man retired.

I spent all my free time working on the assignments for his classes, devouring the books on the suggested reading list, honing my German and Italian so I could read the items that were only available in those languages— perhaps Prof. Elliott would be impressed! Once I ran into him while he was taking one of his long walks, and we circled the campus together, talking about connoisseurship and the detection of fakes and forgeries. I was tempted to “accidentally” meet him more often, but I restrained myself, certain that he valued his time alone.

In May of 1992, during the last weeks of the connoisseurship course, I went to John’s office on a Thursday for one of our usual talks, and he surprised me by shutting the door. “So that we won’t be interrupted,” he said. We stood by the door, gazing at each other in silence as I wondered what was about to happen.

“I have something for you,” he finally said, and drew from his pocket a 1924 edition of Walter Pater’s The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. I knew that book, one of those on the reading list. “You were by far the best student in the class this year,” he told me, opening the book to a passage marked with a ribbon of red silk. He read: Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us in the brilliancy of their gifts is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening.

He closed the book and handed it to me. When I thanked him, my cheeks flushing with pleasure, he said, “You are a brilliant young woman. You’re going to have a wonderful career.”

I was struck dumb by his words, and all I could do was look mutely into his eyes. They were a beautiful color, like the mineral called tanzanite, a rich deep azure. My lips must have parted, because his eyes focused on my mouth, and he suddenly said, “I want very much to kiss you. May I?”

To you his words may seem impossibly courtly and mannered, but that moment was so romantic that I thought I might swoon. I don’t know whether I was able to answer, but he took me in his arms, and put his lips over mine, ever so gently. The memory of that kiss is still so fresh in my mind, these twenty-odd years later, that I can taste him now. He opened his mouth, and his tongue tentatively touched mine, as if in greeting. The kiss grew deeper, and then deeper still, until we broke the contact. Still holding the book in one hand, I put my arms around his neck and pulled him to me again with the singlemindedness of an underwater swimmer reaching for the surface. He responded, his hands around my waist. My breasts were flattened against his chest, and I could feel his erection through the navy serge of his trousers.

Eventually, of course, we had to stop, but I think it was he who gently pushed me away. My memory here is less distinct. My brain was racing, churning. I couldn’t put two thoughts together in a coherent sequence. He told me that he wanted to see me again, but that it mustn’t be here, in his office. Did I want to see him? Oh yes, I said, Yes… John. Although he encouraged graduate students to call him by his given name, many of us never did so, out of the respect in which we held him. That was the moment that I stopped thinking of him as Professor Elliott, and began to think of him as John.

Copyright 2015 by Linnet Moss

Notes: The main narrative in this story is third-person with a limited point of view (Andy’s). But I also gave Andy a first-person voice, through the journal she writes as part of her psychotherapy. What interests me most about my characters is their sexual and romantic histories, and how these affect their subsequent relationships. In this story, I thought it would be interesting to reveal Andy’s memories of falling in love with her husband, even as she reconnects with another man from her past.

The pink sweater falling to the floor is something that happened to me. It was one of those rare moments when you can read another person’s mind, even though not a word is spoken. In real life, it went nowhere, but I never forgot it.

I am really enjoying the historical art perspective. Very cool. I have a dear friend who studied art curation years ago both here and in Italy. Whenever she talks about art, I listen entranced. Wishing I knew more. Great second chapter and I am hooked. A ‘pink sweater’ incidence hey? I need to ponder if ever I too have had one.

I often wish I could have studied in Italy!

Perhaps “pink sweater” moments are treasured more as we get older and they become less common, LOL! But I also think I am more aware of such things than when I was younger and rather oblivious.

I think if i had a professor like John i would have been much more interested in certain subjects.. (but then again i studied finance and nobody like John teaches that stuff sadly…) I do remember however a very Byronesque history professor in highschool, and whaddayaknow i always liked history 🙂

So far i am getting a very sad melancholic feeling from this, but not in a bad way. Sad memories are not necessarily bad memories 🙂

I am curious what they will find in the cemetery.

And i like the sculpted version of the god. You make me crave the V&A and its sculptures and i don’t have time over the next few weeks for a trip there, sigh.

I have never been to the V&A–it’s on my list for my next London trip!!

Yes, this story is more melancholy than my others, but it is also about the sweetness of memory and the comfort it brings.

Those Byronic professors–sigh. I had a dangerous tendency to fall for professors when I was young. Now that I am one of them myself, I am less easy to impress, LOL! But John is a composite of real ones I have known.

oh you have to see the V&A! i like the variety in it and the special things like the massive v old Turkish carpet for which the light goes only for a 1 every 30 min and which is surrounded by old Qurans, or the models of famous monuments i have seen all cramped in a big room, or some of my famous Rodins or the tapestries for the painting of the Sistine Chapel and the inner courtyard which reminds me of Florence 🙂 It is like having some best bits of the World in the middle of London for free 🙂

Oh that was the only prof i found interesting, well apart from the TA i actually dated (while he was my TA, but only in the final part of the final year ;-)).

All the TA’s were too young and callow for me, LOL! But I had a torrid affair with a professor (unmarried).

The Turkish carpet sounds fantastic. I know the VandA also has a lot of miniature paintings, which I would dearly love to see. I even featured them in one of my stories. The Young Man Among the Roses by Nicholas Hilliard is my favorite.

Oh need to see that one, the paintings are the things i’ve seen least at VA yet 😉

And yeah the TA turned out to be too young and working in the same area was not good for his ambitions. Seems a lot of people in academia, especially men want something maybe decorative to show off and enjoy the intellectual fun but not an academic career alongside them. Seems to be the case generally in life i find.

Oh and which one of the stories featured the painting? 🙂

Yes, too many men prefer someone who is not their intellectual equal. A helpmeet rather than a soulmate.

The miniature makes a brief appearance in my “Tastes” trilogy, the first (and most erotic) books I wrote. I think it’s in “London Broil” which is Volume 1. I have mixed feelings about that series–sometimes I think I need to rewrite and improve it, but then again I am attached to the original words because the experience of writing it was so intense.

oh i must go back, this is why it seems familiar then! as i’ve read the first one 😉 Need to go back to it anyway to continue to series!

and yes to the first assessment, very sadly 😦 bane of my life one could say.

I’m enjoying this story very much, honestly. Learning and enjoying all in one 🙂 Oh, university crushes… I had one for my English poetry teacher… we all had, honestly, he was of the kind not-shockingly handsome but irresistibly cute, he ended always the lesson with his jacket dirt with chalk. And he was so passionate when talking about poetry, he made very interesting and beautiful lessons. Oh, Robert Browning and “My Last Duchess”!

Ah, Robert Browning! How romantic… Yes, I enjoyed the sweet, cute professors too, but what always got me was the high voltage brainpower. It is rare but unmistakable. And usually not paired with good looks, but when that happens it’s killer 🙂

My professor was cute, but not as cute as Dr Barker 🙂 https://youtu.be/qlJhrfUaqGU

Haha! Love the sexy black shirt! I never had a prof who dressed like that 🙂

He is cute, kind of like a professorial Hiddles.

“a professorial Hiddles”, I like that! 🙂 Imagine a university with both Prof. Sebelius and Dr. Barker… Hihihihi

The female students, and not a few of the males, would be wandering about lovestruck 🙂 And more people would take humanities courses!

Catching up before I read chapter 3 – was away last week.

Oh, that flashback made me feel butterflies in my stomach. So romantic, and so beautifully described, it was as if I could feel John’s lips closing on mine, and feeling that surge of joy shoot through me that you get when your romantic hopes suddenly become reality…

Now on to ch 3.

Thank you! I’m glad you liked John’s story. I worried about whether it would hold people’s interest, as it does for me. The surge of joy–that’s it exactly.

It totally holds my interest. (And I have never been in love with any of my professors *shudders*, nor have I been in love with a man significantly older than me, but somehow his character really resonates…)

LOL poor deprived thing, you had no gorgeous professors along the lines of Cumberbatch or (be still my heart) Cary Grant? One of the great joys of life is being passionately lectured to by such a specimen of eggheaded masculinity 🙂 I am reminded of Professor Flynn in “Circle of Friends” explaining Malinowski’s “Sexual Life of Savages” to the wide-eyed undergraduates

I can honestly say that there was not a single such specimen in the departments I studied in… They were more of the benign or snarky granddad variety. So not really romantic material 😀

Not even a Michael Caine from “Educating Rita”? Sad, sad, sad! Say, when is RA going to play a professor? I think he should teach a course on Human Sexuality and offer private tutorials 🙂 I want to see him in corduroys, LOL.

Oh Linnet – I had to LOL. That is *exactly* the scenario that my tumblr friends and I spun into a communal fan fiction two years ago. It was all quite silly (but hey, why not). I must look if I can find the links somewhere… BTW, instead of corduroys we dressed him in one of those sexy cardigans. And that was pre-Hobbit press where RA blew us away with his knitwear. *rofl* Maybe he took inspiration from our fiction…

He would be the perfect combination of brain and brawn, delivered in a tweed jacket with elbow patches… and he already reads love poetry 🙂